Biomedical engineers in Australia have invented an innovative high-speed bioprinter that can print copies of human organs using sound, light and bubbles. This could be a real breakthrough in drug production.

Details

Currently, scientists have only limited ways to create tissues for drug testing, and they are mostly complex and expensive and also prone to errors such as misalignment of cells. At the same time, David Collins, head of the Collins BioMicrosystems laboratory at the University of Melbourne and co-author of the new study notes that thanks to the new approach, it becomes possible not only to precisely position cells, but also to manufacture on a scale of individual cells.

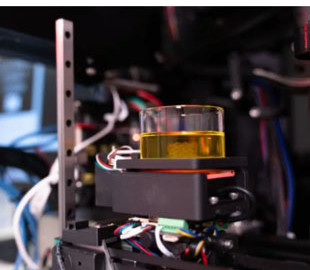

The new printer projects light onto the resin bubble to give it the desired shape, while the speaker emits sound waves that cause the bubble to vibrate. These waves help to position the individual cells and greatly speed up the process. According to the statement, this innovative printing is 350 times faster than traditional methods. Collins explains:

200% Deposit Bonus up to €3,000 180% First Deposit Bonus up to $20,000What we do — we project light in a 2D pattern, and that's what's so special about this technology — we print through a bubble. We're constantly changing these projections, which are building up individual layers as we go. The fundamental principle is that we can shine light on a material and create a solid.

Because the tissue floats in resin during printing, the bioprinter can also create “really delicate structures using really soft materials, softer than anything else currently in use.” The ability to accurately replicate the texture of human tissue is fundamental. Collins adds that they can even print analogs of different body parts, such as bones, tendons and skin.

In addition, the floating tissue does not need to be printed on a solid platform, unlike traditional methods. Instead, it can be printed directly in a petri dish, vial or lab plate. This increases cell survival rates by avoiding the need to physically handle the material, which in traditional bioprinters can sometimes contaminate and damage cells.

So far, the team has only printed tiny tissue samples, and they note that full-scale 3D printing of organs still seems like a futuristic idea.

But the scientists have a bold vision for the future. The technology, the researchers say, could be used to replicate human organs and tissues for more targeted and ethical drug trials, as it would eliminate the need for animal testing. The team next plans to collaborate with the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne to further explore this.