A Montreal company intends to market milk made from cells. The first tests are conclusive, but production in industrial quantities is not for tomorrow.

Open in full screen mode

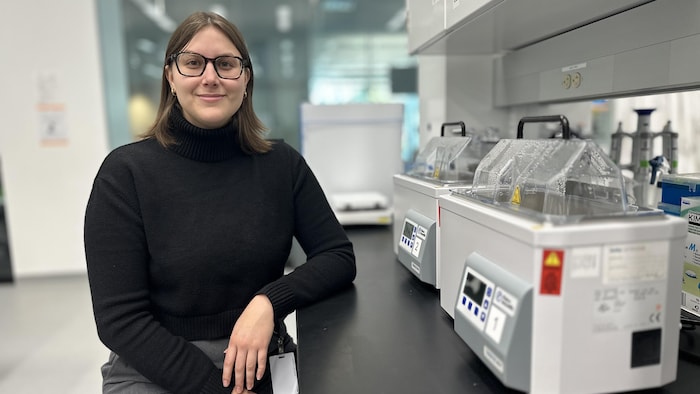

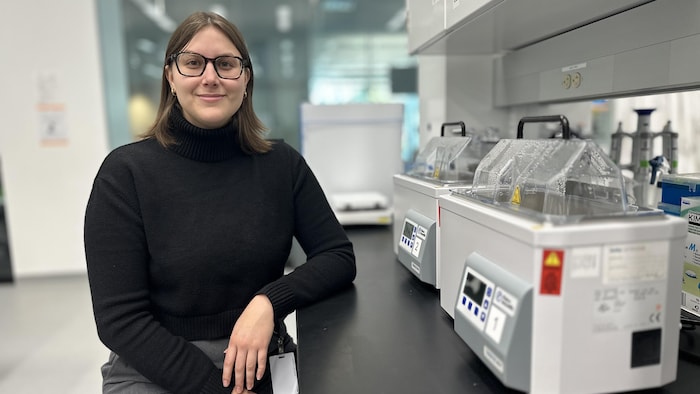

Jennifer Côté is the president and founder of Opalia

- Vincent Rességuier (View profile)Vincent Rességuier

Speech synthesis, based on artificial intelligence, makes it possible to generate spoken text from written text .

“It really tastes like cow's milk, it smells like milk, there's also a little aftertaste on the tongue,” rejoices Jennifer Côté, the founder of Opalia.

A few weeks ago, with her team, this young businesswoman produced her first samples of milk generated from cells. For this first experiment, these are very small quantities.

At the time of our visit, only residues remained and a smell of fresh cheese emanated from the test tube… to his greatest satisfaction. The product evolves like classic milk that would have been produced by a cow, explains Ms. Côté. The components can be functional in a cheese-making process, for example.

Within 4 to 5 years, Opalia hopes to commercialize on a large scale scale of milk grown in the laboratory and intends to find partners to develop derived products, such as cheese or yogurt.

In theory, the principle is simple. Cells are collected from cows on the farm, from milk or from a cell bank. They are then fed with a liquid – itself manufactured in a laboratory – which contains sugar, amino acids, salt or water. In fact, all the elements that make up a mammal's diet.

This liquid, used by Opalia, contains all the nutrients necessary for the growth of cells grown in the laboratory.

The goal now is to produce it in large quantities in an industrial bioreactor, a sterile tank that in appearance resembles the huge tanks used for beer fermentation.

Loading

“We haven't said our last word” in the standoff with Meta, says St-Onge

ELSELSE ON INFO: “We haven't said our last word” in the standoff with Meta, says St-Onge

According to Ms. Côté, her team has all kinds of engineering challenges to overcome, but she has no doubts about the purpose.

Not only does it& #x27;s visionary, but it's necessary, says Bettina Hamelin, CEO of Ontario Genomics, a non-profit organization that supports genomics projects.

She is interested, among other things, in the development of cellular agriculture. Without hesitation, she affirms that this is a sector of the future, because an organic revolution is underway all over the world. She also argues that land intended for agriculture is starting to run out, while the world population is showing sustained growth.

In a report published in 2021, Ontario Genomics estimates that, by 2030, food biomanufacturing could become a $7.5 billion industry and 86,000 jobs in Canada alone.

Ms. Hamelin concedes, however, that many obstacles remain to be overcome, particularly production costs. First, because bioreactors remain expensive and must be imported. Then, because of the high price of the different elements which are necessary for the growth of cells in the laboratory.

Microplates used for milk cell culture

Another delicate step will be obtaining certifications from Health Canada and other regulatory bodies. Currently, only the United States and Singapore allow the sale of lab-grown meat. As is often the case, the Canadian authorities could be inspired by decisions taken by their southern neighbors.

This is currently being done, specifies Ms. Hamelin, Health Canada has a group that deals with emerging industries. There is no shortage of challenges. It is necessary to analyze production methods, product control and microbiological, chemical, physical risks, as well as the impact on consumer health.

A step that doesn't really worry Jennifer Côté, because there are already laboratory-grown products on the food market.

It's not new in fact, explains the young business manager. For example, in cheese there is an ingredient called renin which is used to coagulate milk. This product is made in the laboratory with a fermentation process, much like beer. It's not in the newspapers every day, but we're used to eating it.

When we ask her if her milk will be safe for consumption, she says she has no doubt about it.

Bettina Hamelin, CEO of Ontario Genomics, a non-profit organization funded in particular by the Ontario government and Genome Canada

< p class="StyledBodyHtmlParagraph-sc-48221190-4 hnvfyV">However, we will have to gain the trust of consumers. According to Bettina Hamelin, the main argument remains environmental, because traditional breeding is among the most damaging activities for the environment.

I think that& #x27;consumers must be educated on the benefits of alternative protein production, says the CEO of Ontario Genomics. More and more studies show that energy use goes down by about 90% and there are 90% fewer greenhouse gas emissions. /p>

But caution is required, responds French biologist Jean-François Hocquette, research director at the National Institute for Research on Agriculture, Food and the Environment (INRAE). He reviewed scientific work on cellular agriculture.

French biologist Jean-François Hocquette, research director at the National Institute for Research on agriculture, food and the environment (INRAE)

Regarding the environmental impact of products from cellular agriculture, there are extremely few studies, he explains. To have an incontestable scientific truth, you need a large number of studies which are confirmed by different approaches, by different laboratories, in different countries and there we arrive at a consensus. For the moment this consensus does not exist.

Cellular agriculture techniques are in their infancy today.

A quote from Jean-François Hocquette, biologist

According to the biologist, this sector poses more questions than it gives answers. There is no proof, for example, that the foods will be safe for health, that they will have satisfactory nutritional value, that they will be more economical to produce or that their preparation will be less energy-intensive than traditional livestock farming.

Promoters of cellular agriculture present these technologies as extremely promising solutions or miracle solutions, he continues. But at the same time, they do not provide assurance that they can resolve the nutritional, health or even ethical questions that we ask ourselves today.

He concedes that laboratory cultivation could be a credible option for feeding humanity in the future, but that it will require massive investment in research and development.

Lucas House, scientific director and Jennifer Côté, president of Opalia

Not enough to discourage Jennifer Côté who also hopes to do her part for the well-being of animals, one of the bases of her project.

She is both vegan and a lover of traditional cheeses. Two characteristics that are currently irreconcilable, which is why she no longer consumes dairy products. Lab-grown milk would provide an acceptable solution.

If there are technologies that are available and competitive, why use sentient animals , while in the end we are looking for the final product? she wonders.

It now remains to be determined whether the product that Opalia intends to market will be called milk. It is possible that traditional producers will contest this designation. A question which will then have to be studied by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

- Vincent Rességuier (View profile)Vincent RességuierFollow